I have big concerns about our modern industrial agricultural practices. Sometimes I am prone to angry tirades about chemicals poisoning our food supply and polluting our planet. My main beef (chicken, pig, etc.) is that corporate money-making and production practices have hijacked functions that should be grounded in communities and support environmental health.

Quite frankly, there are a lot of farming practices that must change if we are going to make a dent in our collective carbon footprint and stave off some of the worst effects of human-induced climate change.1)http://report.ipcc.ch/sr15/pdf/sr15_spm_final.pdf.

We also have a lot of work to do to remove toxic chemicals from our food supply. However, I think there’s an even more immediate and pressing concern that needs our attention.

Our farmers need our support now more than ever.

We often think of farmers as just those who grow food in the ground. However, much of the fish that we eat is now farmed. Cotton is field grown, and materials like wool come from farm-raised livestock. Farmed trees provide our nuts, lumber, fuel, and paper products.

Unless you grow 100% of your own food, fiber, wood fuel, and paper products, the reality is you depend on farming activities. And you depend on farmers on a daily basis.

Our farmers are facing monumental challenges that are driving them to desperation, and even suicide, at disproportionately high rates.

Are Farmer Suicide Rates Really Higher Than Other Professions?

You may have read that the Center for Disease Control (CDC) recently retracted a multi-year study that claimed suicide rates in the occupational category called “farming, forestry, and fishing” were significantly higher than for other occupational groups.2)https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/65/wr/mm6525a1.htm?s_cid=mm6525a1_w

The data was called into question because of possible coding errors in categorizing the professions associated with the term “farming.” Farm workers, for example, would fall under that occupational grouping. However, people operating farms in a management capacity would fall into the “Management” occupation category.

As a result, farm management suicide data may not be represented in that term “farming.” Therefore the claim that suicide rates are 4 to 5 times greater among “farmers” might not be entirely accurate. A complete re-coding of the data is underway. So, we don’t yet know what the newly coded data will show.

Farmer Suicide Around the World

Nonetheless, around the world (not just in the U.S.) there is significant data that indicates farmers have become an at-risk population for depression and suicide.

Let’s look at a few examples.

India

In India, farmers are committing suicide at a disproportionate rate to the rest of the population. The primary cause of suicide among farmers is related to excessive debt, coupled with crop failures and crop pricing being too low to cover costs. Drinking pesticides is one of the most common methods of committing suicide among these farmers.3)https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2210600615300277

France

In France, farmers are killing themselves at least 22% more often than the general population. That figure is likely an underestimate because farm deaths are often characterized as accidents so that surviving family members can receive life insurance benefits. As in India, excessive debt, crop failures, and falling prices seem to be the primary reasons for these suicides.4)https://www.nytimes.com/2017/08/20/world/europe/france-farm-suicide.html

United Kingdom

In the U.K., about one farmer a week commits suicide. This, too, is a disproportionately high rate relative to the rest of the population. Isolation, stress from external factors like weather and crop prices, and debt are also primary reasons for this trend in the U.K.5)https://www.yellowwellies.org/keep-minding-your-head/

Developing Countries

Although the data is not as clear in developing countries, there is plenty of anecdotal evidence to suggest that these are not isolated examples. In developing countries—hardest hit by climate change, devastating resource wars, and extreme poverty—the risks may be even greater.

According to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), “between 2005 and 2015, natural disasters cost the agricultural sectors of developing country economies a staggering $96 billion in damaged or lost crop and livestock production.”6)http://www.fao.org/news/story/en/item/1106977/icode/

Those kind of losses in countries already in desperate conditions have most certainly had a negative impact on farmers’ mental health.

What’s Driving Farmers to Suicide at Alarming Rates?

Even though there are disputes about the extent to which farmers commit suicide relative to other occupational groups, there’s growing agreement that this is a real and lasting problem. Researchers around the world have been trying to understand the forces at work making members of this profession more at risk.

The Agrarian Imperative, Interrupted

Farmers tend to be very hardy people. They often live in isolated areas. They work long days doing physically demanding work.

Farming is also a very dangerous activity according to the CDC.

Farmers are at very high risk for fatal and nonfatal injuries; and farming is one of the few industries in which family members (who often share the work and live on the premises) are also at risk for fatal and nonfatal injuries.7)https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/topics/aginjury/default.html

Farmers sustain themselves through mental and physical challenges because they find meaning in their work.

Many farmers have what psychologists call an “agrarian imperative” or a very strong desire to supply others with the food or resources that they need to sustain their lives.8)https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2017/dec/06/why-are-americas-farmers-killing-themselves-in-record-numbers

Unfortunately, when circumstances beyond farmers’ control—such as changes in the financial markets or weather catastrophes—interfere with their ability to perform their agrarian imperative, farmers are at greater risk for loss of meaning and depression.

Farmers are, by the nature of their work, independent and resourceful people. These qualities can make it difficult to recognize the need for—and to ask for—help.

Financial Crisis

Farming today is not a self-sustaining activity. It requires large investments in equipment and infrastructure. There are huge costs associated with seeds and fertilizers. For organic farmers, those costs are even higher, and yields are not as easy to achieve.

To be competitive, farmers have had to scale up their operations. As a result, when failures occur, the losses tend to be monumental. For example, two recent hurricanes, Florence and Michael, have devastated farming operations across North Carolina and Georgia.

Just in those two states, agricultural losses are estimated to be about $2.5 billion. Roughly 5.4 million chickens and turkeys died from flooding and hurricane damage. Vast quantities of field crops were flooded and uprooted.

In Georgia, pecan trees were destroyed. Since pecan trees take 10 years to produce a useful crop, pecan farmers suffer the fallout from these events for years to come.

Farm Aid Falls Short

Most people believe that crop insurance and farm aid packages will atone for these losses. The reality is that small- to mid-scale farmers often receive only a limited share of the available aid. Compensation is usually not commensurate with their losses.9)https://newfoodeconomy.org/2017-natural-disasters-agriculture-damage-5-billion/

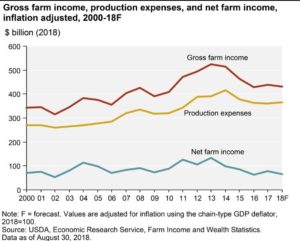

Also, many affected farmers have no personal financial resources to draw on during emergencies. According to the USDA:

Median farm income earned by farm households was estimated at -$800 in 2017 and was forecast to decline to -$1,691 in 2018. In recent years, slightly more than half of farm households have had negative farm income each year.10)https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/farm-economy/farm-household-well-being/farm-household-income-forecast/

The only reason these farmers get by is because they have off-farm jobs. Many only continue to farm because they have loans and need to keep their farms operating to cover debts.

These few facts are just the tip of the iceberg on the data that is available about farm income declines and losses around the world. However, an even more disconcerting trend is that farmers who do manage to stay in the business are forced to adopt dangerous, industrial practices.

Loss of Independence

The number of U.S. farmers has stabilized at about 2 million since the 1970s. The amount of land in use has also stabilized. However, productivity has almost doubled as a result of “improvements in technology.”11)https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/ag-and-food-statistics-charting-the-essentials/farming-and-farm-income/

GMO seeds, synthetic fertilizer, stronger herbicides and pesticides, and heavy equipment make this possible. Raising livestock in high-density environments and excessive fossil fuel use are also at work.

Farms are becoming more efficient at a great cost to our shared environment and our health. The data surrounding the harm to us all, as a result of industrial farming practices, has caused some of us to lose faith in our farmers and turn some of our anger at abuses toward the people who raise this food.

Corporate Contracts

Yet, the truth is that farmers are just responding rationally to market demands. Once upon a time, farmers may have been able to raise chickens and sell them to their local grocery store at a fair price. However, today, farmers have to sell to corporations, like Tysons or Costco, to get their chickens to stores.12)https://www.npr.org/sections/thesalt/2017/06/22/533944458/farmers-take-out-millions-in-loans-to-raise-chickens-for-big-box-retailers

To qualify to work with these corporate buyers, farmers must modify their farming to comply with the corporate requirements relating to raising out those chickens. They also have to accept the price the corporation offers. Those prices necessitate the use of practices that most of us wouldn’t consider wholesome.

Technically, these corporate contract farmers are still “independent.” Yet, they no longer get to make independent decisions about their farming practices.

The reality is that many farmers aren’t happy about some of the practices they are forced to employ. But they have to do what’s necessary to keep their farms. Those farms are also very often their homes, which have sometimes been in their family for generations.

This isn’t just happening with chicken farming. Almost all field crops and other livestock transactions have either actual contract-based requirements or implied requirements. If farmers fail to follow these procedures, or don’t take advantage of the “technology improvements” available to them, they will not be able to keep farming.

It’s easy to point to the harm in farming. Yet, when you look closely at farmers’ motivations for their choices, we can see that they are just like most of us. They are trying to make a decent living in a system that is rigged against them.

Negative Stereotypes and Loss of Community

Even though it actually takes savvy people to navigate the complexities of the farming business today, farming is no longer considered a skilled profession. Instead farmers are seen as laborers and machine operators. Or worse, they are viewed as evil perpetrators of environmental damage.

Children of multigeneration farming families are leaving rural communities in pursuit of higher-paying, more respected professions, at exodus-level rates. With no young families to continue the farming tradition, and fewer jobs available due to improved technology, rural communities are declining.13)https://www.ers.usda.gov/webdocs/publications/85740/eib-182.pdf?v=43054 These factors lead to even more isolation in an already isolated profession.

Negative stereotypes of farmers and failing rural communities may not be primary contributors to high suicide rates. However, in an already stressful profession, not being respected for your contributions can certainly add to your sense of despair. Watching your communities collapse, and knowing that your children don’t want to follow in your footsteps, can also be extremely disheartening.

Chemical Exposure

Another theory that sometimes comes up is that exposure to pesticides and herbicides are contributing to farmers’ mental health issues. This theory is tricky. In truth, we are all likely exposed to these toxic chemicals at levels that are probably much higher than is healthy.

Antidepressants, in fact, are one of the most commonly used drugs among persons 12 years and older, according to the CDC.14)https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db283.htm Personally, I suspect our toxic food supply has a great deal to do with this.

Farmers, though, who use chemicals on their farms are actually more well-educated about the risks than, say, the average lawn grower using Round-up. Farmers use protective gear. They follow guidelines for exposure to the letter of the law because they are legally required to maintain their pesticide licenses.

Dicamba Dilemma

That being said, as old chemicals decline in usefulness against super weeds and insects, new chemicals are introduced. More intense, less-well-understood chemicals are being applied without fully vetting the intersection of risks to crops and farmers.

For example, drift damage from supposedly safe applications of Dicamba has destroyed crops on farms where the chemical was not even used.15)https://www.cornandsoybeandigest.com/weeds/measure-dicamba-risks If unsprayed crops can be killed by unexpected drift, then farmers may also be subject to exposure at unintended levels.

Pesticides and Depression

At least one significant study has shown links between pesticide applicators and increased risk for depression.16)https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19079725 Pesticide applicators are not necessarily “farmers.” They could, for example, be landscapers. Regardless of job title, the study concluded that “both acute high-intensity and cumulative pesticide exposure may contribute to depression in pesticide applicators.”

Depression does not necessarily lead to suicide. Still, when you factor in potential for increased levels of depression from pesticide use and all the other challenges farmers are facing today, it starts to add up.

Making Sense of All This Data

I am not a psychologist, scientific researcher, pesticide expert, economist, or any other kind of expert on this subject. I am just a homesteader and environmentally conscientious person trying to make sense of this information. Honestly, though, the plight of our farmers concerns me deeply, particularly in the age of climate change.

Just in the past few years, I have read story after story of loss and hardship. I have seen it with my own eyes in my community here in rural North Carolina and around my state.

I don’t want to turn our farmers into victims or martyrs. Because, honestly, the farmers I know are some of the most caring, resilient, and hard-working people around. Also, farmers are not the only people impacted by financial, cultural, and climate-related challenges. Yet, I think that, given farmers’ importance in our daily lives, we do owe them some special consideration.

How Can We Help?

Figuring out how to best help our farmers, while transitioning to more sustainable food-saving practices, is an incredibly complex undertaking.

Many of us consumers are also struggling to make ends meet. We might want to buy only fair-purchase-price foods and support only organic practices, yet we can’t always fit those choices into our budgets.

Changes have to come on many fronts, and they will take time. Some of them will have ripple effects in all of our lives. Yet, we need to get there.

Here are a few ideas to get you started thinking on these things:

1. Stop Blaming Farmers

For starters, let’s stop vilifying our farmers even when they use GMO seeds and spray toxic chemicals.

Corporations have driven farmer dependence on these products. Government policies have facilitated corporate infiltration of farming practices. And, as much as we don’t like to admit it, consumer support for low-cost products from big corporations has reinforced these actions.

Let’s put the blame where it belongs—on corporations, on governments, and on ourselves to the extent that we benefit from these systems. Let’s challenge these institutions and make the best choices we can as consumers.

2. Support Sustainable Farmer Policies

As a food-conscious community, we need to support leaders and policies that facilitate transitions to sustainable farming.

Big business likes to claim that small farmers can’t feed the world. This is untrue. The fact is that small farmers already feed 80% of the world.17)http://www.fao.org/news/story/en/item/260535/icode/

Big business just reaps a disproportionate financial benefit from their small share of the world’s provisions. Through a very elaborate global distribution scheme, big business has managed to make large fortunes off the labor of our farmers.

This has to stop!

Farmers deserve a fair share. Subsidies should not go to corporations, but directly to farmers who work to improve their environment and offer food and resource stability to their direct communities.

Policies should be geared at transparency so that we, as taxpayers and consumers, know where our subsidies go and where our food comes from.

There is a lot to be done in this area. But, raising our awareness of the issues and giving our support where it counts is key.

3. Support Local Distribution

We need local co-ops and grocers who are willing to source farm-based products from local farmers. And we need them to do it in large enough quantities to make it sustainable for farmers. Then, we as consumers need to be committed to shopping at these outlets.

Please support your local farmers’ markets. But also lobby your grocery stores and farm product suppliers to demand local goods. Or, form your own buyers’ clubs to source from local producers.

4. Grow Your Own Groceries

Food is not the only thing farmers sell. Heirloom seeds, composted manure, straw, hay, mulch, livestock, and more are all products of farming industries. Even when you grow your own food, you still have plenty of opportunities to source your inputs directly from farmers.

Also, when you do go to the trouble to raise your own food, you have a deeper appreciation for what it takes to produce these products. This understanding translates into a greater appreciation for the work that farmers do.

We Want to Hear From You!

I feel as if I have barely made a dent in presenting these issues. Hopefully, though, this has gotten you thinking about our farmers, sustainable farming, and the actions you can take in your community.

We’d love to hear your thoughts and ideas in the comments below.

And if you are a farmer… THANK YOU! WE NEED YOU!

Tasha Greer is a regular contributor to The Grow Network and has cowritten several e-books with Marjory Wildcraft. The author of “Grow Your Own Spices” (December 2020), she also blogs for MorningChores.com and Mother Earth News. For more tips on homesteading and herb and spice gardening, follow Tasha at Simplestead.com.

References

| ↑1 | http://report.ipcc.ch/sr15/pdf/sr15_spm_final.pdf |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/65/wr/mm6525a1.htm?s_cid=mm6525a1_w |

| ↑3 | https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2210600615300277 |

| ↑4 | https://www.nytimes.com/2017/08/20/world/europe/france-farm-suicide.html |

| ↑5 | https://www.yellowwellies.org/keep-minding-your-head/ |

| ↑6 | http://www.fao.org/news/story/en/item/1106977/icode/ |

| ↑7 | https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/topics/aginjury/default.html |

| ↑8 | https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2017/dec/06/why-are-americas-farmers-killing-themselves-in-record-numbers |

| ↑9 | https://newfoodeconomy.org/2017-natural-disasters-agriculture-damage-5-billion/ |

| ↑10 | https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/farm-economy/farm-household-well-being/farm-household-income-forecast/ |

| ↑11 | https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/ag-and-food-statistics-charting-the-essentials/farming-and-farm-income/ |

| ↑12 | https://www.npr.org/sections/thesalt/2017/06/22/533944458/farmers-take-out-millions-in-loans-to-raise-chickens-for-big-box-retailers |

| ↑13 | https://www.ers.usda.gov/webdocs/publications/85740/eib-182.pdf?v=43054 |

| ↑14 | https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db283.htm |

| ↑15 | https://www.cornandsoybeandigest.com/weeds/measure-dicamba-risks |

| ↑16 | https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19079725 |

| ↑17 | http://www.fao.org/news/story/en/item/260535/icode/ |

COMMENTS(1)

I had no idea about farmer suicide. That’s so tragic. Thank you for sharing. Personally, I’m inclined to blame the pesticides. But I know I’m starting with a bias.