Welcome to the Organic Growers’ Tool Kit Series

Tool #7: Good Water Management

In this series, so far, we’ve covered these critical tools for building soil and growing healthy vegetables in the mean time.

- The importance of organic matter in building soil.

- The mason jar test to discover your soil texture type and leveraging that information to grow more food.

- At-home soil tests to manage plant health while you build soil.

- Nitrogen fertilizers that don’t wreak environmental havoc or derail your soil building efforts.

- Mycorrhizael inoculant to unleash the phosphorous and potassium in your garden and boost your yeilds.

- Re-mineralizing your soil with rock dust to provide trace minerals and expedite your soil’s transition to the promise land of loam.

In case you missed any of these topics, check out the rest of the series.

Read More: Organic Growers Tool Kit Series

Applying these tools in your garden will radically improve your results, increase the nutrition in your vegetables, and save you much of the frustration most new gardeners suffer.

Correction … these six tools will do all of that as long as you use them in conjunction with tool #7.

Without Tool #7, Tools #1 Through #6 Will FAIL!

Without effective use of our organic grower’s tool #7, none of those previous 6 tools will matter in the long run. Yikes!

Luckily, tool #7—a key ingredient in soil and plant health—is so simple, most people just fail to give it the consideration it deserves when starting and planning their gardens.

I am talking about water management. To soil, the right amount of water is life. Yet, in the wrong amounts or coming from a contaminated source, it can mean death both to soil life and to all your hopes of a healthy garden.

Water Is Critical to Soil-Building and Soil Life!

Luckily, with a little know-how, you can manage this precious resource in your landscape and use it to effectively build soil and grow food with minimal work.

You have probably heard people say that most vegetables need about an inch of water a week. This is a shorthand way of helping gardeners figure out how much to water. In most gardens, with less than loamy soil or insufficient organic matter, though, this figure is flat-out incorrect.

You may have also heard that you should water only the root zone around plants to prevent fungal diseases. This, too, is well-meant advice.

It works for large farming operations where drip tape is cheap and soil-building is secondary to plant production. However, it’s downright wrong when your fundamental goal is to transform your dirt into thriving soil so you don’t have to use industrial growing methods in your own backyard.

The ‘Best Birthday Cake’ Approach to Watering

I’d like to give you an alternative way of thinking about how and when to water your soil:

- First off, if you want to build soil, you must water your soil. As in, all of it!

- Second, you must apply as much water as is needed, as often as is required, to keep soil perpetually moist but not boggy.

In other words, your soil will be like the freshest, most perfect, moist and spongy birthday cake you’ve ever had. Well-watered soil should feel like a daily celebration of all the life forms that call it home.

5 Reasons Why Soil Moisture Is So Important

Before we get into strategies for harnessing the power of effective watering in your garden, let’s look at 5 reasons why maintaining soil moisture is so important.

#1: Oasis vs. Large Resource Rich Land Mass

All life forms that exist in soil need water to function—from the fungi, to the protozoa, to the bacteria, insects, nematodes, and everything else you can imagine.

If you only water your plant roots, and not all of your soil, then those life forms will only do their work where you water.

You effectively make your plant roots an oasis in a desert.

Each time you harvest those plants, you also then destroy the oasis. Survivors have to stick it out in small pockets of moist soil until you start watering your next plant oasis. And, quite frankly, not all of them make it.

This means that each time you turn over your beds, you are risking all your efforts to build healthy soil. By watering all of your soil—and not just the root zone of your plants—you instead make large, connected land masses of resources available for plants to draw on as needed.

Soil life continues with minimal disturbance even when plants are harvested, because they are not bound to a single plant’s roots. They also have the infrastructure in the soil to move from root zone to root zone across a connected land mass. Even when disturbances occur, they don’t automatically mean a death sentence to your soil-building efforts.

#2: Water Weathers

If you’ve ever walked on a rock with divots that fill with water in the rain, then you know the power of water to weather inorganic materials. Water does this in your soil, too.

Water breaks down bits of rock into smaller bits that can then be used by soil life to make nutrients available to plants. It also decomposes the skeletons of insects into manageable sources of calcium that will eventually feed plants.

Without the weathering power of water, many of the inorganic materials in soil could not decompose into manageable sizes to be used by soil life and plants.

#3: Nutrients Are Water-Soluble

Many of the nutrients plants use are only accessible to plants when they are made water-soluble. This means those nutrients must be dissolved in water to be taken up by the roots. Water is the transmission method for nutrients.

Without sufficient water to make nutrients digestible by plant roots, they might as well not exist in the soil.

#4: Water Is the ‘On’ Switch

Lay a pile of viable vegetable seeds on a dry surface. What happens?

You got it. Nothing at all!

Now, lay those same seeds on a wet paper towel, and at least some of them will germinate. Well, seeds aren’t the only things activated by water. Some of the other forms of soil life are only active when wet.

Like all those mycorrhizael good guys covered in tool #5, without water, they are as dormant in soil as they were in the bag they came in. If you want beneficial bacteria and fungi to do their work in your soil, you need to keep them active. Maintaining moisture in your soil is the only way to do that.

#5: Soil Compaction and Erosion

Soil that dries out for an extended period of time is going to develop 1 of 2 conditions.

It will either become compacted because, without water to create spaces, particles mush together and form almost unbreakable bonds. This is what happens in clay soil.

Or, it will dry out and erode. In soils that are silty or sandy, water is like the glue that holds things together. Without the right amount of water, those particles become loose and subject to loss from winds, heavy rains, and other forms of disturbance (e.g., tilling).

Have Your Cake (Like Soil) and Eat From It, Too!

Hopefully, I’ve convinced you of the importance of water in building soil and growing a healthy garden. Now, let’s dig into some ways of having your cake-like soil and getting a great harvest from it, too.

The only way to do this effectively is to have a 2-pronged approach to water management.

- First, you need to have a method for getting water to all of your soil (i.e., rain or watering).

- Second, you also need ways of maintaining ideal levels of moisture in your soil.

The rest of this article will cover some ideas to help you maintain the right volume of water in your soil. These ideas will make frequent irrigation less necessary.

Then, next time, we’ll look at ways to make irrigation easier depending on the size of your garden, quality of your soil, and frequency of rain in your area.

Moisture Management Strategies

There are very few of us who get the perfect amount of rain for growing a vegetable garden. We either get too much, too little, or too erratic rates of rain to rely 100% on the weather for watering. This means that we’re going to need to apply strategies for keeping our soil “best-birthday-cake moist” at all times.

Strategy #1: Create Good Drainage

“Good drainage” is one of those terms that often gets used in relation to the requirements of plants that are highly susceptible to root rot and other fungal conditions. Since most of our common garden vegetables fall into this category, you see it a lot in growing guides for veggies. But what does it really mean?

Good Drainage in Relation to Soil Texture Type

Good drainage in relation to soil actually means that the soil has the ability to retain a lot of water before it becomes swampy. Loam-type soil, because of the particle size of soil components and its high organic-matter content, has the capacity to store a lot more water without becoming water-logged than clay or silt can.

Sandy soil, on other hand, has excessive drainage and doesn’t hold enough water to supply most vegetables what they need.

Simply by adding organic matter, such as compost, and covering bare soil with mulch, you can improve drainage in clay, silt, or sand soil.

Good Drainage in Relation to Garden Design

The term good drainage in relation to garden design means that you’ve taken steps to ensure your soil either drains or holds water appropriate to your soil texture type and your climate and weather conditions.

In clay soil, it might mean that you’ve built your beds on a slope, or mounded them, to help water escape from the root zone. In sandy soil, this might mean that you’ve added some kind of irrigation system to ensure moisture during dry periods.

In soil-less conditions, such as excessive rocky areas or erosion zones, you may have to use things like raised beds and hugelkulturs in your garden design to achieve good drainage.

Planning for Good Drainage

The strategies you use to ensure good drainage should always be designed in relation to your current soil texture type and your prevailing weather conditions.

In wet areas, you need to facilitate more drainage. In dry areas, you need to increase water holding capacity and plan for irrigation alternatives.

In areas that oscillate between too wet and too dry, you need to do a bit of both. In most cases, some combination of these three strategies will work for your conditions.

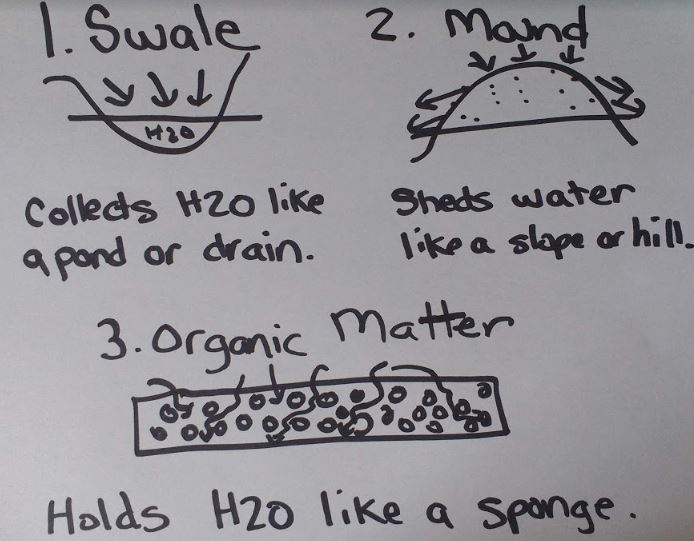

Swales

In dry areas, planting in swales—or depressions in the earth—can funnel more water into the earth as a drain would. The shape also helps drive water deeper into the earth so it’s available to soil life. Plus, swales tend to collect organic matter that runs off from higher areas, which can increase water-holding capacity, too.

In wet areas, swales can be used to catch water and store it away from the direct root zone of tender plants.

Mounds

Mounds are swales in reverse. Rather than collecting more water, they force it to run off the sides so areas don’t become boggy. Also, the mounded shape increases surface soil that is exposed to the air and can increase drying time after heavy rains.

Mounds can also be used to direct water into other areas to prevent flooding or force it into swales. This is similar to what people do when they use sandbags to protect their homes during excessive rain or water flow.

Organic Matter

Organic matter, in both of these scenarios, adds holding capacity, regulates drying time, and supports soil life. By using organic matter along with swales or mounds, as appropriate to your conditions, you can manage water flow even in extreme conditions.

Strategy #2: Use Appropriate Vegetation

The truth is, even when you plan for good drainage, sometimes conditions are simply too extreme for the drainage designs and organic matter you put in place.

For example, we got 22.5 inches of rain in a 30-day period this summer. Our swales soaked it up and our mounds whisked the rain away as planned. However, with 30 days of cloud cover and no sun to dry things, swales and mounds alone would not have been enough to restore order to our soil after a rain event of that magnitude. The right vegetation in the right place at the right time proved key.

In our case, sweet potatoes and winter squash vines saved our soil from suffering extended waterlog. The plant roots were in raised, mulch-covered mounds and so were safe from rot.

The vines, however, grew to epic lengths, acting as umbrellas channeling rain away from soaked beds. As they rerooted in new locations, they also acted like straws, drawing excess moisture from the soil and channeling it into more leaf growth and fruit and root production.

Likewise, in August and early September when we had absurd heat and dry conditions following all that rain, purslane pulled its weight by cooling and protecting the soil around some of our more drought- and heat-sensitive plants, holding in all that earlier moisture.

Keeping your garden planted at all times, even in winter, and incorporating adaptive plants into your crop rotation can help maintain the water levels in your soil. When periods of excess moisture or dryness happen, then leave all that extra foliage on your beds as mulch and organic matter so nutrients are not lost.

In our area, extreme rain and extreme drought are both real risks, particularly in summer and winter. So we always plant at least half our garden in “hedge our bets” kind of plants to ensure we have something growing even when conditions are extra challenging.

For summer, we use amaranth, oak leaf lettuce, sweet potatoes (for vines and roots), purslane, hardy strains of winter squash or pumpkin, and chard. For winter, we use winter wheat, garlic, leeks, green onions, mustard, kale, daikon, and parsnips to provide moisture stability in our soil.

By incorporating survival crops that grow well in your most extreme conditions, along with more tender crops, you can preserve moisture in dry times and harness it in wet times. Overgrowth can also become mulch.

Conclusion

Deal with your drainage using good design and all the soil improvement tools we’ve covered in this series so far. Also, plant plenty of resilient, adaptable plants to help maintain moisture. And tune in next time to take a look at irrigation strategies that will help you build soil without breaking the bank (or your back)!

What Do You Think?

How much thought have you given to the amount of water that flows through your garden? Do you have strategies for managing excess water or dealing with dryness? What’s your biggest water challenge? Please let us know your experiences and your thoughts on water as life for your soil using the comments below.

Tasha Greer is a regular contributor to The Grow Network and has cowritten several e-books with Marjory Wildcraft. The author of “Grow Your Own Spices” (December 2020), she also blogs for MorningChores.com and Mother Earth News. For more tips on homesteading and herb and spice gardening, follow Tasha at Simplestead.com.

COMMENTS(1)

The conclusion mentioned further irrigation strategies. Could you please tell me which article is being referred to?